Candyman (2021) | Review

Mirrors have forever been an invitation to invoke spirits of the dead and to tempt darkest fate—whether one is chanting Bloody Mary’s name or gazing Narcissus-style into the abyss of one’s own vanity. Whatever the conduit, there’s no doubt they work great in the visual medium of film. Looking glasses have factored heavily into the genre from 1931’s Dracula (the absence of a reflection to confirm the absence of a soul) to 2008’s Mirrors (where whole, horrible worlds lurk beyond the glass). Candyman (1992) is perhaps the best-known and best-loved of these, so needless to say the long-awaited, oft-postponed upgrade is creating quite a buzz. (Pun intended: the bees are back, too!)

Candyman takes place in present-day, a decade after the last of the infamous Chicago Cabrini-Green towers projects were torn down to make way for slick, pricy, gentrified artists’ lofts. Fine arts painter Anthony McCoy (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) and his gallery curator girlfriend Brianna Cartwright (Teyonah Parris) have recently moved into one of the designer flats and are soon informed of the high rise’s bloody past.

Brianna’s brother, Troy (Nathan Stewart-Jarrett), tells them the tale of too-curious grad student Helen Lyle and her run-in on the property with Candyman (nee Daniel Robitaille), the vengeful ghost of a Black artist and son of a slave who kills those who summon him by saying his name five times in a mirror. Anthony is intrigued and hunts down a longtime Cabrini-Green resident, old-timer William Burke (Colman Domingo) who tells him about a 1977 Halloween scare in which a Candyman incarnate, Sherman Fields (Michael Hargrove), was secreting razor blades into the kiddie’s candies. He goes on to imply that it could be time for the restless spirit to find another human portal from which he can wreak some of his trademark hook-handed havoc, warning Anthony to be careful.

At one point, the film switches to Brianna’s point of view as she deals with the discovery of slashed bodies at the art gallery, which reminds her of witnessing her mentally ill father’s suicide—but her state of mind doesn’t factor in otherwise, making the segue feel somewhat jarring. Then there’s a scene showing Candyman killing a few high school bullies while their victim cowers in a bathroom stall—I don’t know who these people were or how they factor into Anthony’s story, which probably doesn’t matter since they’re never mentioned again.

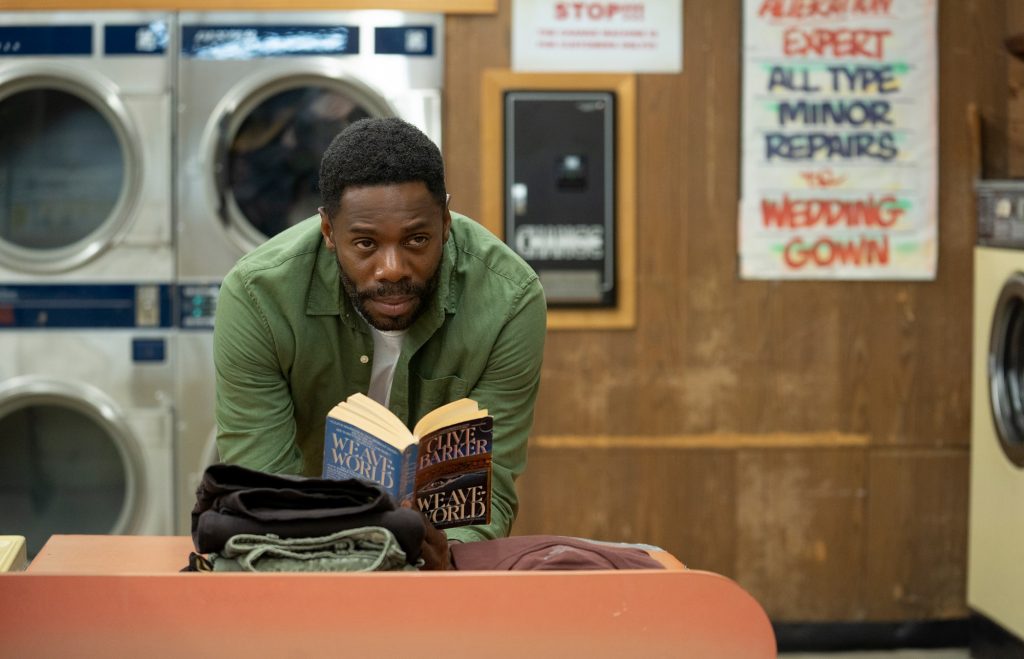

Candyman, aside from using the goofy Sammy Davis, Jr. song of the same name in the prologue, is not played for laughs at all. There’s also a distinct lack of animal magnetism; Tony Todd, who originated the role and makes a cameo here, was a commanding, awe-inspiring creature with a seductiveness to him reminiscent of Count Dracula, and he commanded his bees to do his bidding, but that’s not the case here. There are a couple of winks to original, though, and there are nods to Candyman’s creator, writer Clive Barker: one of the characters shares his first name, and when Anthony goes to pick Burke’s brain, the older man is reading a paperback of Weaveworld. (If you’re a fan who loves the original Candyman, be sure and check out our exclusive, extensive tribute to it on its 25th anniversary.)

Director Nia DaCosta does a satisfactory job here, but there’s a lack of “voice”—even from co-writer and producer, Jordan Peele. I would have liked some of the arch, darkly humorous spice of Get Out and Us thrown into this horror honeypot, but alas, when all is said and done, this story is pretty one-dimensional. There’s not even much of a feel of Chicago here; the story could have been in Any City, USA. (But maybe that’s the point; it’s a blanched Chi-Town, gentrified to the point of bloodlessness.)

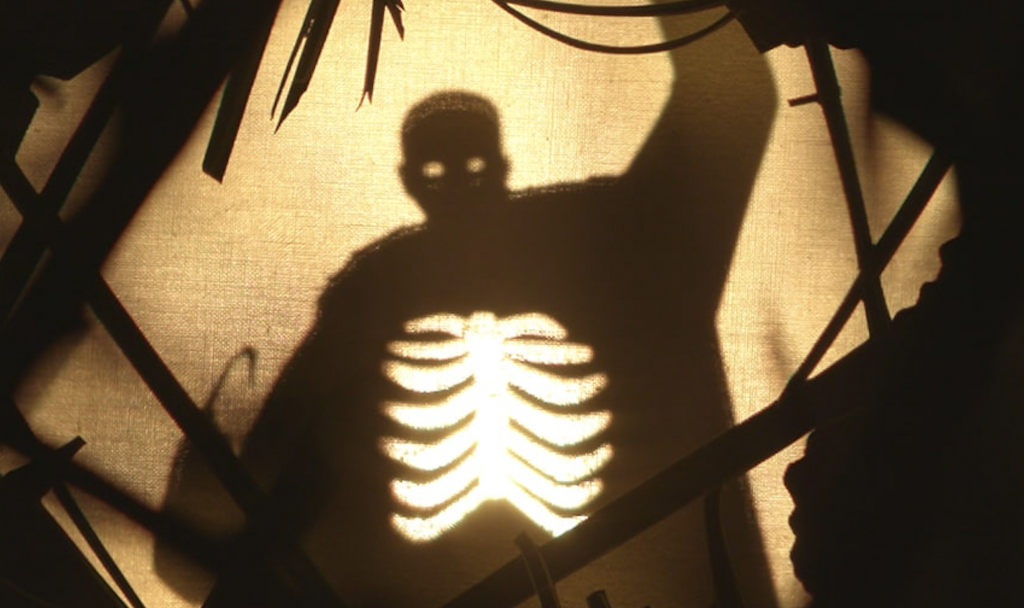

The cinematography is elegant and fluid, while the flashbacks are effectively rendered as shadow puppets. Much of the violence is shown in the reflections of mirrors (one is Anthony’s installation art at a chichi gallery, while another is a teenage girl’s powder compact lying open on a school bathroom floor), and is wrought by mostly unseen hands. This is effective to a point, but in a way, it’s also indifferent. After Anthony is stung by a bee and that sting becomes infected, creeping flesh, we are treated to some gruesome body horror. But again, it feels impersonal (unlike, say, David Cronenberg’s remake of The Fly) because the afflicted man doesn’t seem especially affected. The gore is abundant, but there’s no suspense leading up to it—it just is. In the first film, Candyman glided gracefully, his cloak unfurling and his bees swirling; in this one, he literally floats above the ground, which is cool, but it also disconnects him from our world.

Thanks to its sleek, upscale presentation and its lean hour and a half runtime, Candyman never wears out its welcome and leaves an adequately spooky, if not particularly striking, impression.